Just a Place

The Rational and the Strange in Milton Keynes

MArch Thesis, University of Cambridge, 2023, 20,000 words

Abstract

This thesis sets out to bridge the gap between the historical context, architectural intentions, and lived experience of the 1967 new town of Milton Keynes, UK. It’s architects, tasked with envisioning a new everyday life; merged modernist ideals, American urbanism, and English landscape mythology. British modernism was revealed not as a pursuit for purity, but as a strange and socially progressive vision out of crisis. The principles of autonomy, resilience, and joy were borne out of the architects anxious hesitation to define how future residents should live.

Amid a desire for multi-functionality and deliberate ambiguity, the architects would also integrate the familiarity of the British suburb. As a rare result of meaningful employment under the welfare state, this hybridised typological design thinking was to point the way in post-war Britain. A time where experimental and grounded architecture would serve the public good. It is hard to believe Milton Keynes was ever built.

Now home to around 300,000 people, did the ‘flexible’ new town manage to emancipate it’s citizens? Or did it fall victim to the same rigidity of previous modern new towns? We are still learning from Milton Keynes, it’s approach to architecture, and its lived consequences. Through archival findings, documented lived experience, and interviews with residents and original architects; this research reviews the imaginative potential of the city’s quasi-rational planning and use of incompleteness, relative to its surprising, strange, and uncanny experiential outcomes.

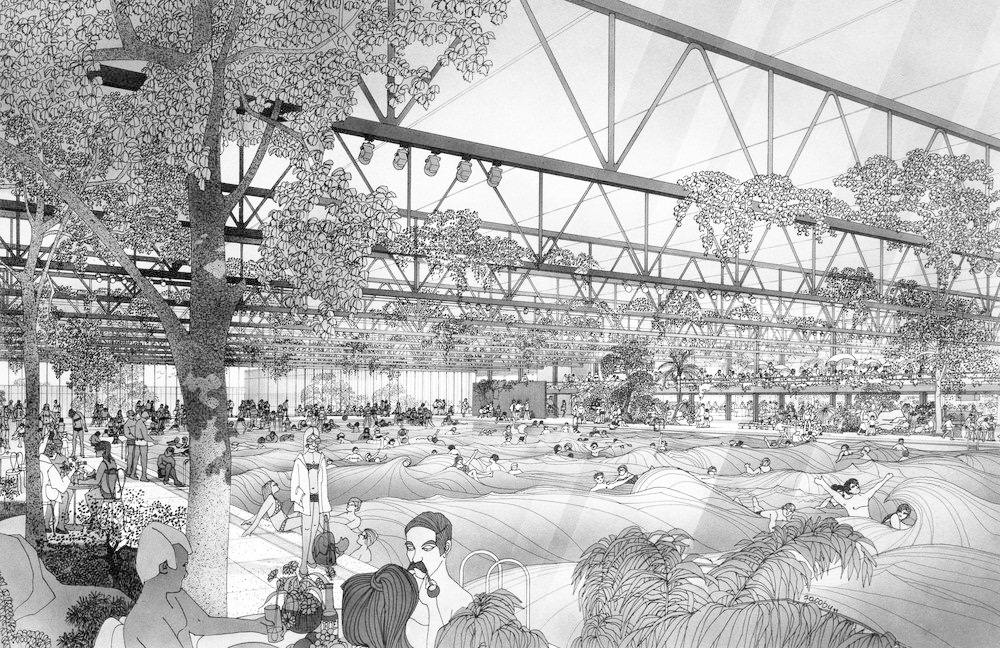

Helmut Jacoby for MKDC, City Club Milton Keynes

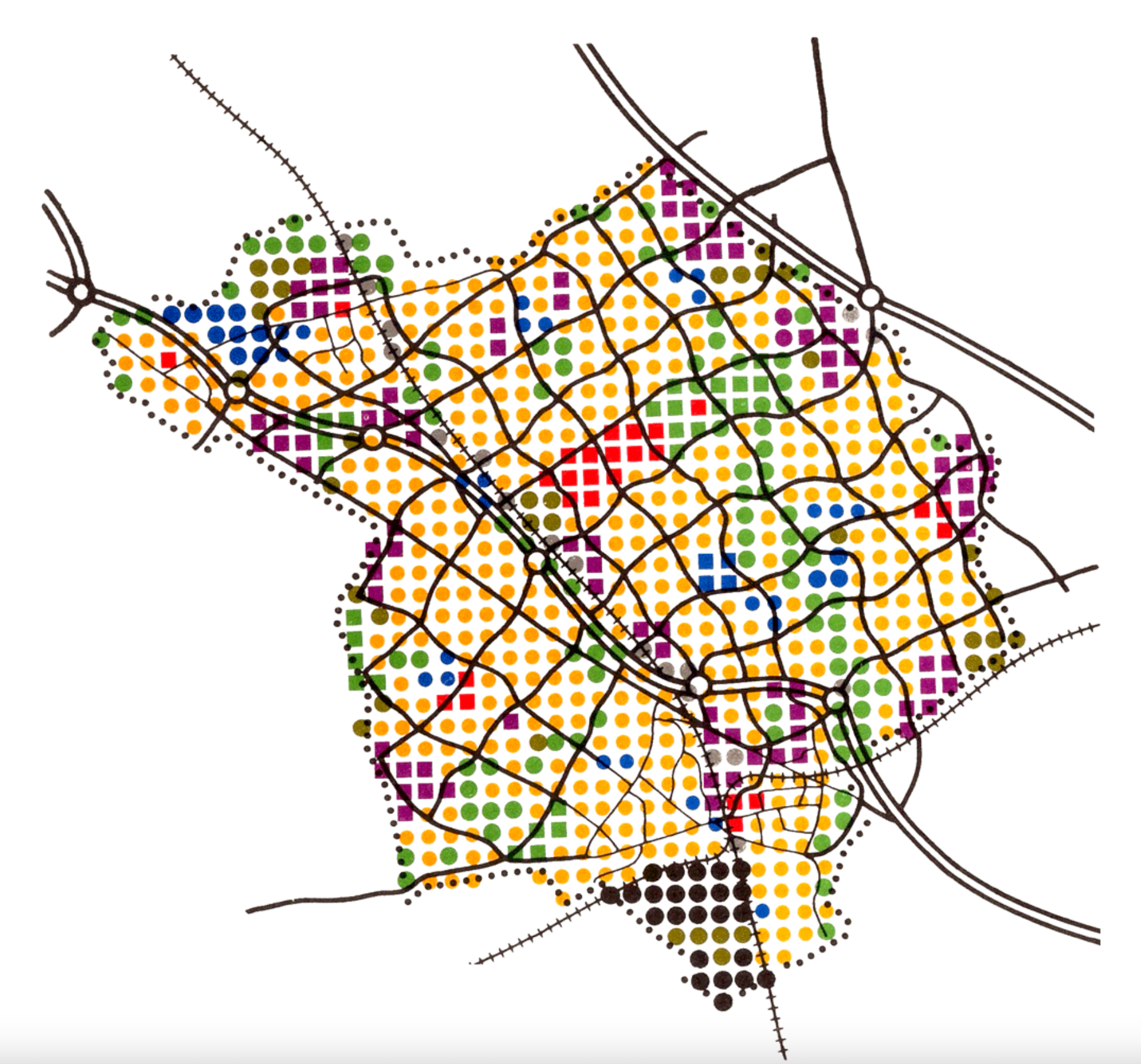

MKDC, Milton Keynes City Plan

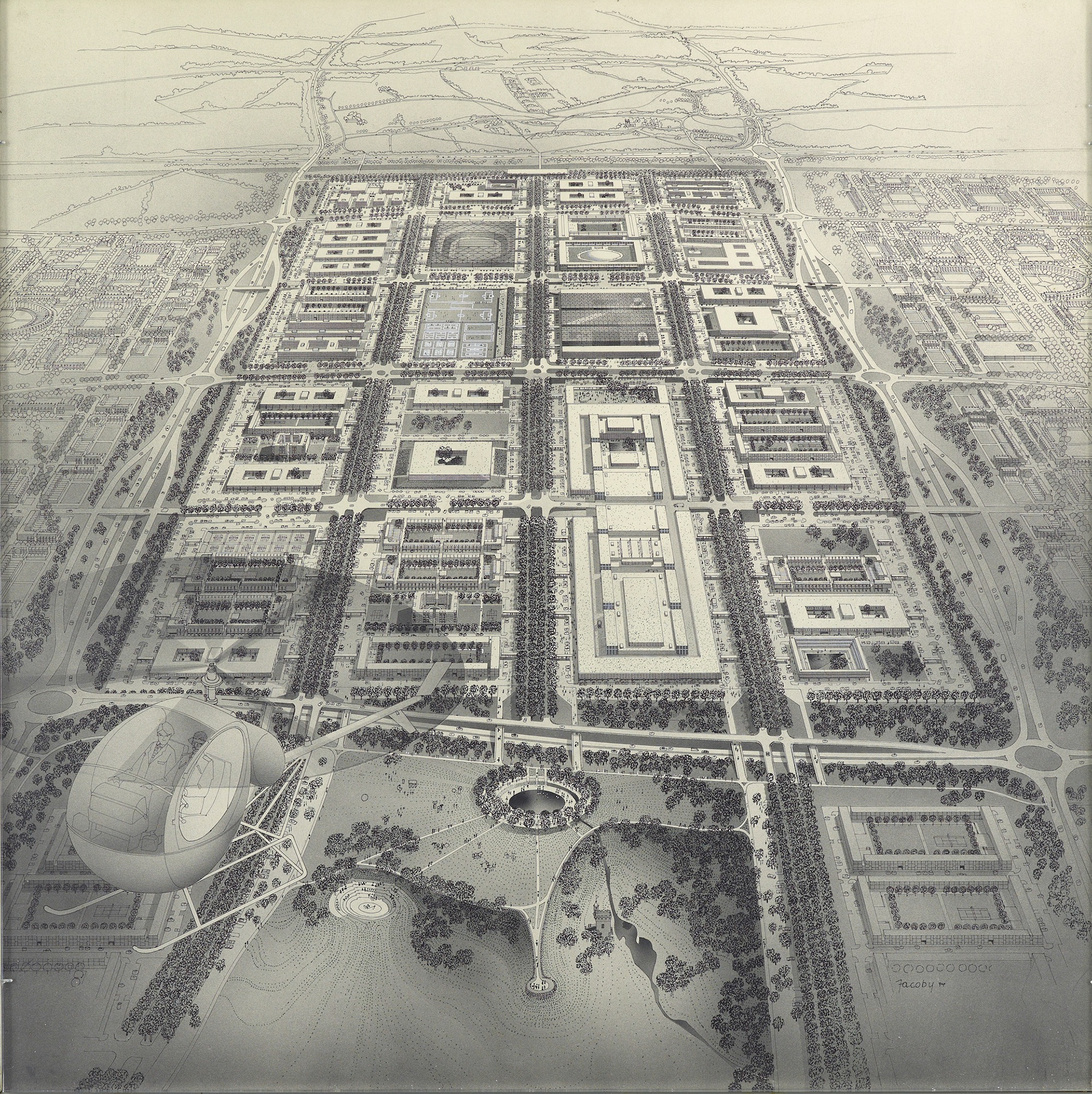

Philip Castle for MKDC, Leisure in Milton Keynes

Helmut Jacoby for MKDC, Milton Keynes

Boyd & Evans, Situation Comedy

Boyd & Evans, Underpass

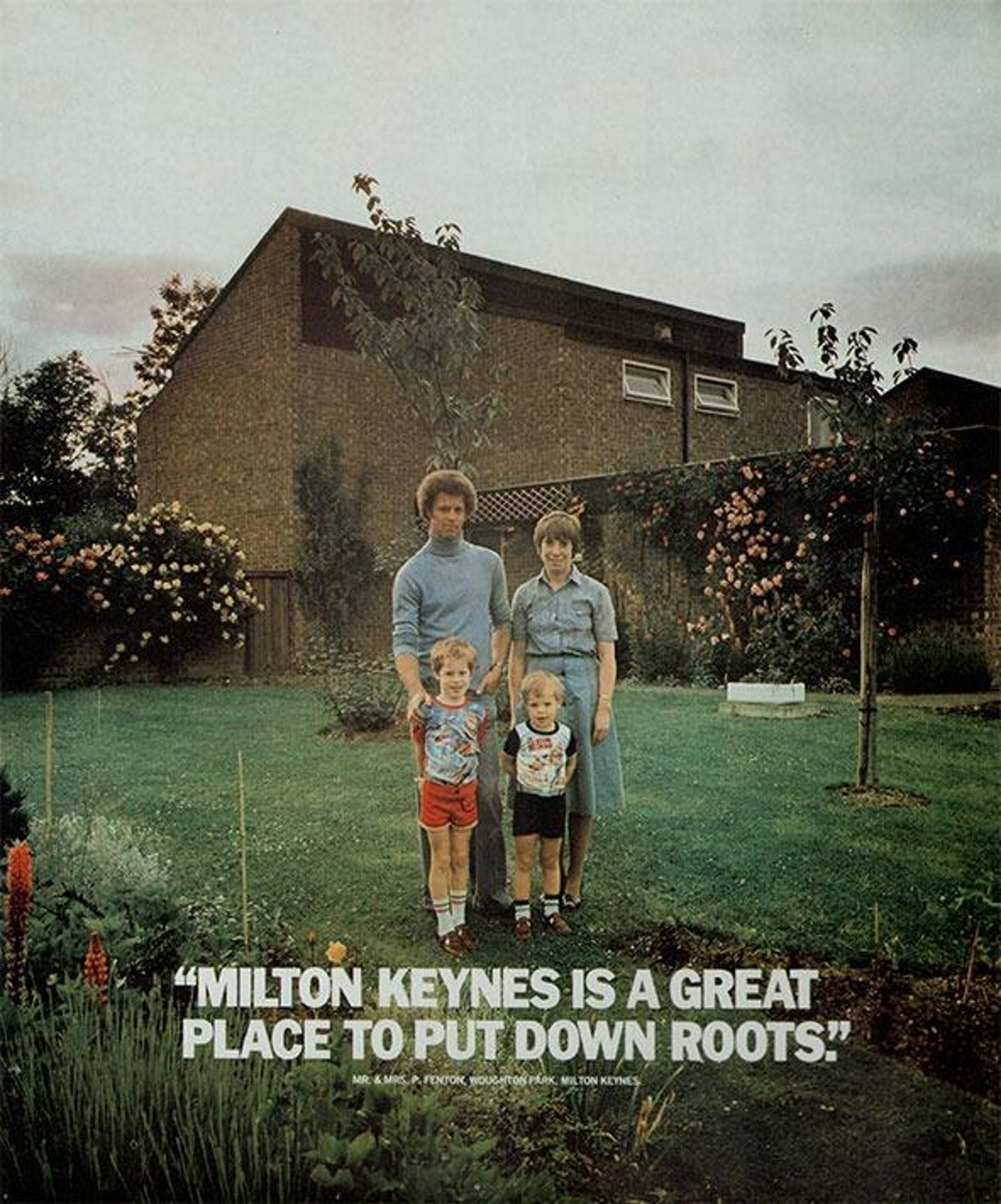

MKDC Marketing

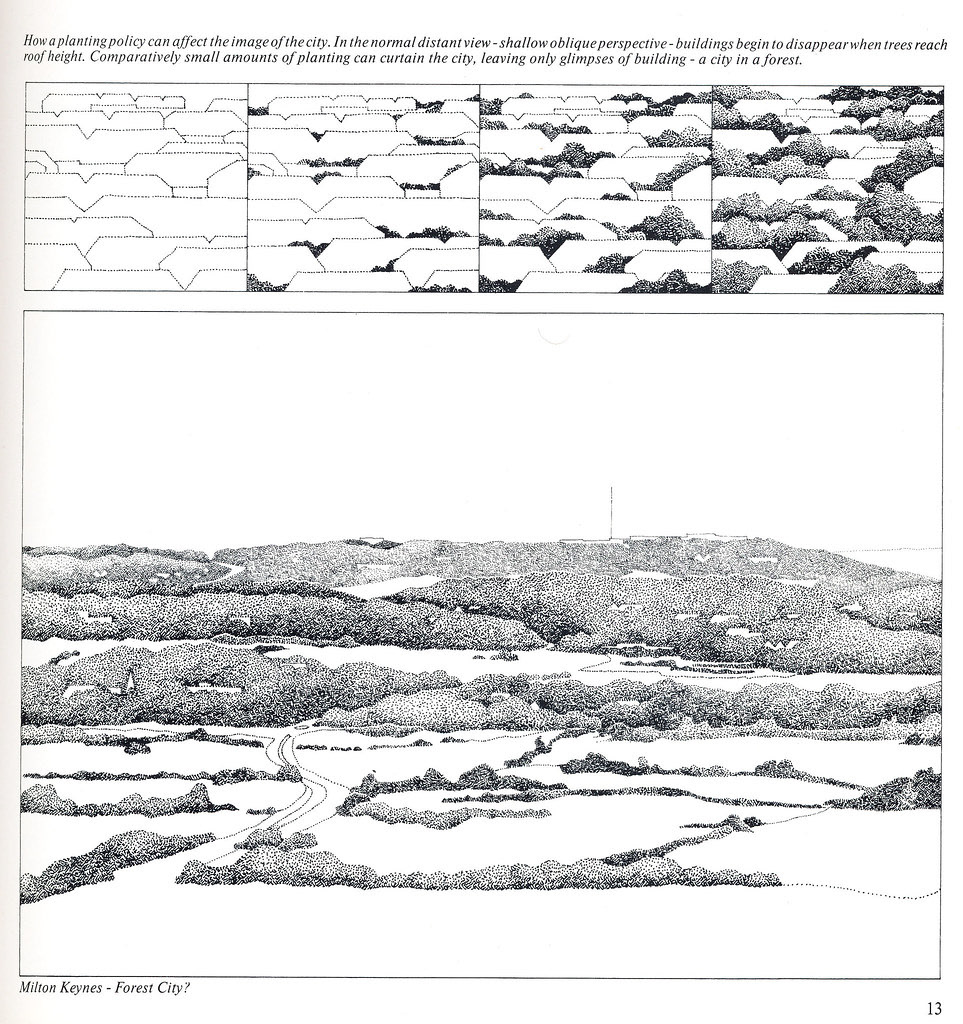

MKDC, Forest City?

Extract from Chapter 3

Architectural Absence

‘Something is uncanny – that is how it begins. But at the same time, one must search for that remoter “something,” which is already close at hand.’ (Ernst Bloch, A Philosophical View of the Detective Novel)

With “no fixed conception of how people ought to live”, these modest architectural intentions meant for a ‘determined uncertainty’ to underpin the urban strategy of Milton Keynes. This ambivalence left the Milton Keynes Development Corporation hesitant to define the new town within public imagination, creating a void that opinion and popular culture were happy to fill. This void then was inherently attached to architectural intention, and with that, ideologically bled into the task of materialising a new town “from scratch”. Today, the inherent ambiguity of Milton Keynes so far discussed in earlier chapters through its transitional identity, as well as its scale-less and incomplete fabric (ideologically and physically), still reflects this initial void. The city is slow and visibly hesitant to reveal itself for the diverse social structures that have emerged there. Short-term visitors to Milton Keynes may only see it as an empty rationalism still waiting for visible appropriation. ‘For skateboarders, towns such as Milton Keynes were perceived as having ‘no real identity’, where culture is alternatively disjointed or non-existent, and where security cameras are endlessly reshooting the most interesting of feature films: everyday life.’ (Borden, Skateboarding and the City)

In reference to a walking tour one undertook with MKDC architects Tim Colesbourne and Peter Martin, Colesbourne made it clear in conversation that the exact alignment of the city grid with the midsummer solstice is in fact just another myth, and is in fact misaligned by approximately a month in testing it through his own experience. It can be said that this misalignment/alignment myth even more accurately represents what chief architect Derek Walker states as the city's prime quality: "its ambiguity." Non-mainstream religious groups such as pagans, witches, wiccas, and modern druids have long thrived within Milton Keynes regardless to the facts of these myths. In conversation with Wendy Pankmurst, or ‘Wendy Witch’ as she is known in the city, Pankmurst is a self-employed spiritual practician who organises pagan weddings (Handfasting), tarot magic spells, and baby naming ceremonies. As one looks for a small clearing in the trees when approaching the narrow-boat to which her and her partner live along the Grand Union canal in Milton Keynes, it’s difficult to comprehend that this secluded haven of docked narrow-boats along a quiet canal, known rather informally by the owners as the “long wet village”, is a 5-minute drive from the Miesian mirrored architecture and American boulevards of the city centre.

The role of architecture here for practices such as skateboarding and non-mainstream religious ritual is one of apparatus, device, and instrument for these individuals and groups to imaginatively utilise in the pursuit of a vitalised and fantastical reality. A means to do something different and personal. The functionally subversive nature of these urban practices can be relayed in the disruption of familiar expectation, quoted here by a local skateboarder: “Empty of cars, car parks have only form and no function.” If Iain Borden is to believe that the culture and act of skateboarding is a practice of critique towards the absence of meaning in the architecture of ‘zero-degree’, then one would ask if there is a possibility here to consider an architecture that rather than being defined only through function, instead defines only space and through the effect of ambiguity, both experientially and visually prompts for critical and imaginative ways of seeing. In line with what the architects of Milton Keynes have contributed to this study in their original intentions, how are we to take the perceiver (future inhabitant) seriously in the discipline of architecture? We may think upon an architecture that isn’t overly determined, and intelligent in its simplicity. An architecture that is incomplete in definition, and thus subordinate to the content it cannot simply foresee or comprehend.